The Invention of Sound Recording: How Vinyl Records and Gramophones Changed the World

The soft crackle of a vinyl record and the whirring of a spinning disc beneath a metal tonearm—these sounds once signaled not only music, but a technological revolution. The invention of sound recording didn’t just bring symphonies and jazz into living rooms; it created a global industry, set new standards for audio fidelity, and became a cornerstone of modern culture. Vinyl records and gramophones made music portable, collectible, and, above all, personal.

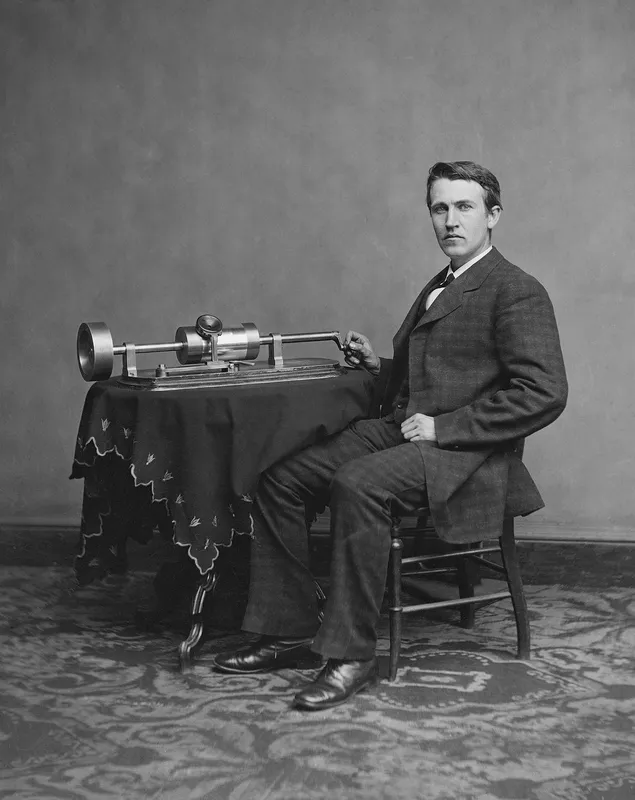

Thomas Edison posing with his original phonograph, the world’s first device for recording and playing sound, 1878. Public Domain. Wikimedia Commons

From Tinfoil to Shellac: The Early Days of Sound Recording

The first practical device to record and reproduce sound was Thomas Edison’s phonograph, invented in 1877. Unlike earlier mechanical toys, Edison’s machine used a grooved cylinder wrapped in tinfoil. When someone spoke or sang into a mouthpiece, vibrations from the sound waves moved a stylus, etching a physical representation of the sound onto the rotating cylinder. Playback reversed the process: the grooves moved the stylus, which recreated the sound through a diaphragm and horn.

Edison’s original phonograph was mostly a curiosity—its recordings were faint, scratchy, and hard to reproduce in large numbers. Yet the concept inspired a race to improve and commercialize the technology. Within two decades, cylinders gave way to flat discs. Shellac records, stamped in mass quantities and played on increasingly sophisticated machines, swept across the world.

The technical limits were clear but impressive for their time. Early cylinders could record just a few minutes, while shellac records (the direct ancestor of the modern vinyl) eventually offered up to five minutes per side. Fidelity was limited, but the magic was undeniable: for the first time, music and voices could be stored, replayed, and even sent across the globe.

Early 20th-century Edison Standard phonograph, showing the classic cylinder design for recording and playback, 1900s. CC BY-SA 2.0. Wikimedia Commons

The Gramophone Era: Spinning Discs and Mass Entertainment

A major leap came with Emile Berliner’s invention of the gramophone in the late 1880s. Berliner’s system used flat discs instead of cylinders and a lateral (side-to-side) groove for encoding sound, which allowed for easier duplication. Shellac discs could be pressed in large quantities, making recorded music accessible to an unprecedented audience.

The first commercial discs spun at 78 revolutions per minute (rpm) and held about three to five minutes of audio per side. Playback was purely mechanical: a steel needle, heavy tonearm, and a resonating horn. By the early 20th century, factories on both sides of the Atlantic churned out millions of discs and machines. Gramophone companies, like Berliner’s in Montreal, Canada, built state-of-the-art facilities to produce, master, and ship records across continents.

This era also saw the development of electric recording, which arrived in the 1920s and dramatically improved audio quality. Now, orchestras, crooners, speeches, and even comedy routines could be heard in living rooms from New York to Paris to Tokyo. The mass production of gramophone records and players fueled a new culture of music appreciation, record collecting, and even the rise of pop stars.

Emile Berliner, inventor of the gramophone, poses with an early disc-playing phonograph, a key milestone in sound recording, 1897. Public Domain. Wikimedia Commons

Matrix Room, Berliner Gramophone Company, Montreal, QC, 1910. Public Domain. Wikimedia Commons

Berliner Grammophon, Hannover. Public Domain. Wikimedia Commons

Manufacturing, Sound Quality, and the Rise of Vinyl

The golden age of shellac records and wind-up gramophones stretched from the 1890s to the 1940s. But as the music industry matured, engineers and inventors pushed for better sound, longer playtimes, and easier manufacturing. Vinyl, a flexible and durable plastic, began to replace shellac after World War II. This innovation allowed for finer grooves, which meant more music could fit on each side and playback could be quieter, with less surface noise.

The classic “LP” (long-playing record) spun at 33 1/3 rpm and could play for more than 20 minutes per side. The 45 rpm single became the format of choice for radio hits and jukeboxes. Hi-fi record players and turntables, now equipped with electric motors, precision tonearms, and magnetic cartridges, brought a new level of clarity to home listening. Record pressing plants became technological marvels—steam-driven or electric, with workers in white coats assembling discs, inspecting for quality, and boxing millions of albums for global shipment.

Recording studios evolved too, from basic setups to high-tech environments equipped with multi-track tape, microphones, and mixing boards. By the mid-20th century, entire genres of music—from jazz to rock and classical—were distributed primarily via vinyl records, and owning a collection became a marker of taste and status.

Assembly room at Berliner Gramophone Company in Montreal, where early record players were built and tested., Montreal, QC, 1910. Public Domain. Wikimedia Commons

Factory floor with skilled workers and heavy machinery, part of early record player manufacturing., Montreal, QC, 1910. Public Domain. Wikimedia Commons

Wall of records in a radio station library, representing the scale of music archiving in the era of vinyl. Public Domain. Wikimedia Commons

Legacy: From Home Listening to Interstellar Travel

By the 1970s, vinyl records and record players were at the heart of home entertainment worldwide. From North America to Europe, Asia to Africa, the black disc became an icon of culture and creativity. Despite the arrival of cassette tapes, CDs, and digital audio, vinyl never truly disappeared. Today, the format is celebrated for its “warmth,” its tangible artwork, and the rituals of needle and groove.

Perhaps the most poetic tribute to vinyl’s legacy came with NASA’s Voyager Golden Record. Launched into space in 1977, this gold-plated disc carries music and sounds from Earth, intended for any intelligent life that might find it. Sound recording had gone interstellar.

Modern audiophiles still prize turntables and vinyl, fueling a global revival in production, collecting, and appreciation. Record stores, once thought obsolete, thrive once more. The story of vinyl records and gramophones is far from over—it is a living testament to human ingenuity, connection, and the endless pursuit of better sound.

NASA’s Voyager Golden Record, the gold-plated disc sent into space in 1977 as a message to the cosmos.. Public Domain. Wikimedia Commons

Modern stereo turntable playing a vinyl record, symbolizing the lasting impact of this technology. Author Jörg Schubert. CC BY 2.0. Wikimedia Commons